Total reset

Wéber Gábor

/

2026.01.23

Wéber Gábor

/

2026.01.23

One of the biggest rule shake-up in Formula 1’s 76-year history arrives this year—so wide-ranging that its real-world consequences are genuinely hard to predict. With so many variables in play, new opportunities also open up: teams may leap forward, or extend an existing advantage. What will be the main engineering challenges in this new rule set—and what will it demand from the drivers? How different will Formula 1 feel compared to what we’ve known so far?

Aerodynamics and Bodywork: Smaller, Lighter, Less Downforce

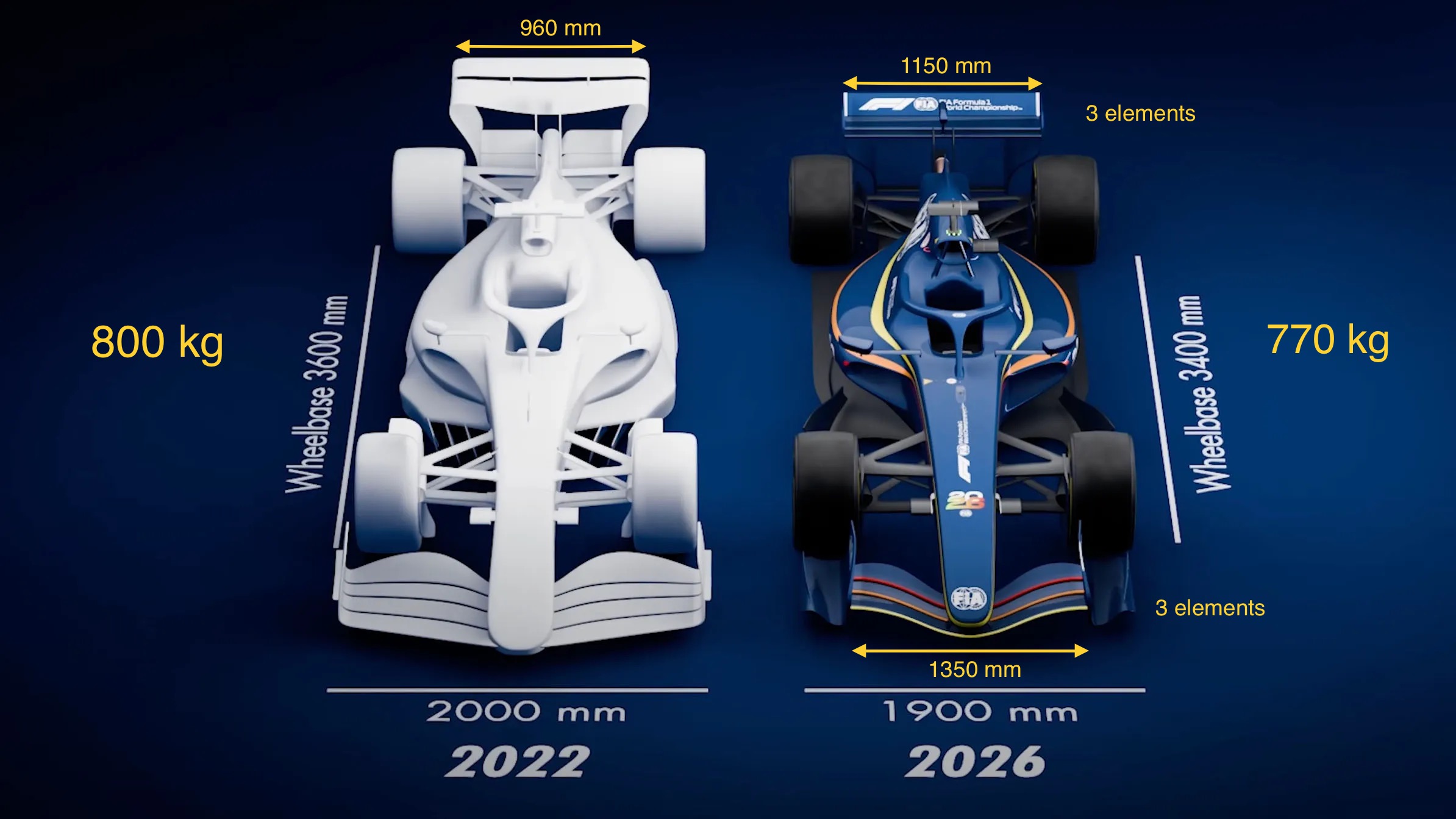

The 2026 cars shrink across the board. They will be shorter, narrower, and lighter than the current “second ground-effect era” F1 machines. Wheelbase reduces by 20 cm, overall width by 10 cm, and minimum mass drops by roughly 30 kg, to about 770 kg depending on minimal tyre mass.

Despite the continued use of 18-inch wheels, the tyres themselves also get smaller. Diameter changes only slightly (720 mm → 705 mm - front, 710 mm - rear), but width reduces noticeably (front 305 → 280 mm, rear 405 → 375 mm). That represents roughly a 10% loss in tyre surface area, with an inevitable impact on cornering grip.

A notable detail: from this year, the regulations separate the nominal tyre mass (46.4 kg per set) from the car mass (724/726 kg), and the two together define the minimum weight (770.4 kg→771 kg). In the technical rules, the race/qualifying mass is effectively defined via the car-plus-tyres total, while Pirelli’s tyre weight could be adjusted without rewriting the rulebook—useful if increasing loads force tyre reinforcements during the season. Another logical consequence is that cars will no longer risk falling below the minimum weight due to tyre wear, as the nominal tyre mass will always be excluded from the car’s weight and handled separately. As a result, post-race tyre pick-up routine may become unnecessary.

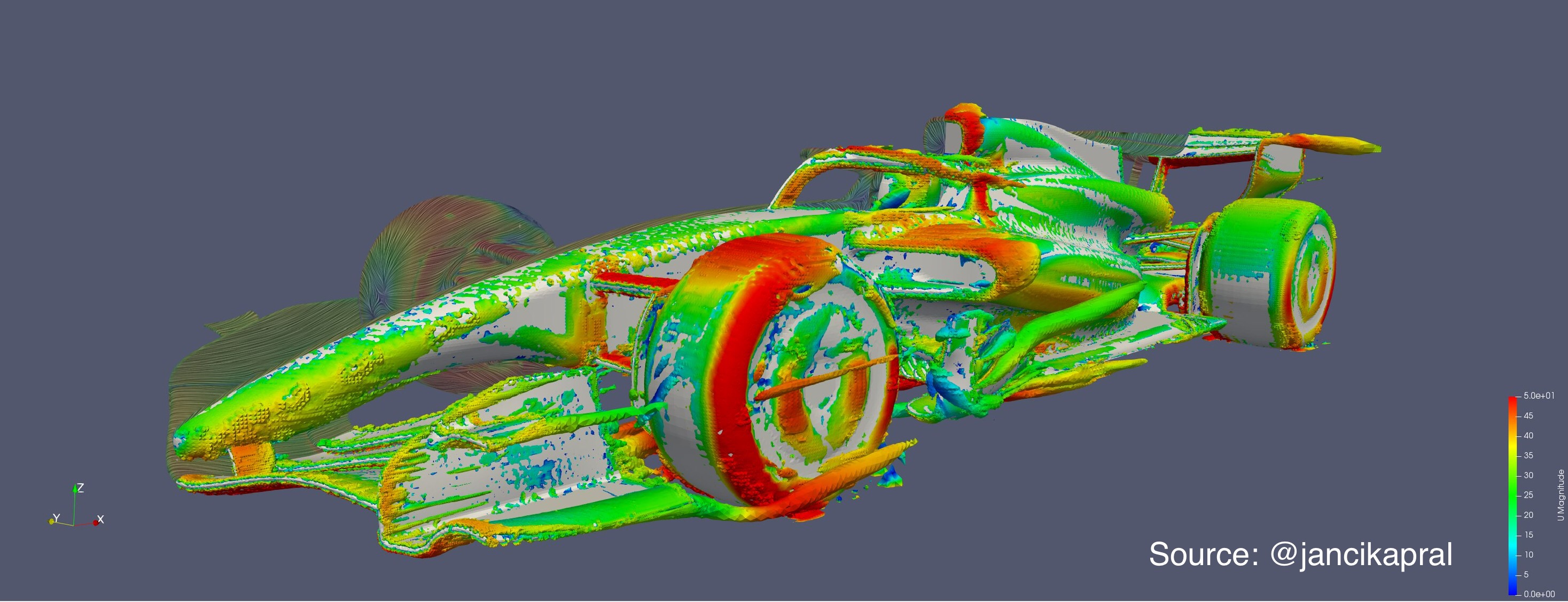

The dimensional changes are not only mechanical; they reshape the aerodynamics too. The biggest shift is underneath the car: the Venturi tunnels disappear, replaced by flat, stepped floor sections on both sides. That significantly reduces the suction (ground-effect) generated under the floor.

Up front, the front wing is reduced to three elements, with a deeper “spoon” profile in the centre. Only the central 135 cm is allowed to generate meaningful downforce. The endplates close off the wing near the inner plane of the wheels, while the outboard flow-control devices fill the permitted width on both sides.

At the rear, the wing now mounts on two pylons, sits lower, but becomes wider (960 mm → 1150 mm) and expands to three elements. The lower beam wing is no longer allowed—replaced by a far simpler supporting structure. Diffuser height and volume are reduced, and the effectiveness of brake-duct winglets is curtailed as well.

Narrower cars and tyres also reduce frontal area, improving drag—something that becomes crucial as teams try to optimise energy usage. One of the headline changes is that an active aerodynamic system replaces DRS. Instead of opening a single rear flap, the new system allows front and rear wing elements to open in sync on (almost) every straight (the upper two elements, front and rear). F1 estimates up to 55% drag reduction in the open state compared to 2025 — an enormous step for straight-line speed and efficiency.

Because the car will run “normal” wing configuration mainly in corners and grip-limited sections, on many tracks the wings will be open for a large portion of the lap. That forces engineers to balance two aero specifications at once—high-downforce cornering vs. low-drag straight-line efficiency—while still developing the car continuously.

This also introduces a new dimension beyond “track-specific” setups: sector-specific optimisation. In plain terms: which flat-out but twisty sections can be taken fastest with how much downforce reduction? That’s a simpler problem at Monza than at Baku, Qatar or Silverstone—especially once energy recovery considerations enter the picture. As in the DRS era, open-wing efficiency will vary between teams and could become an even bigger performance differentiator.

In the “normal” (closed-wing) state, teams may be able to focus more purely on downforce generation, since corner exits will be followed by wing opening anyway—making aero efficiency somewhat less critical there than it used to be. That might also mean less aero configuration variaton between venues.

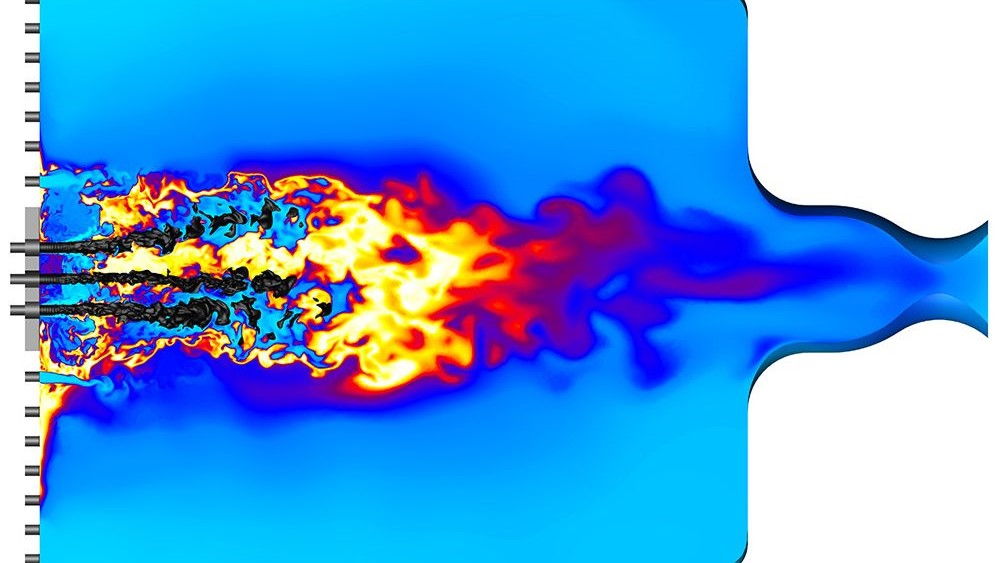

The rules also reshape wake management: with inwashing front-wing and floor boards, cars are encouraged to draw more of their turbulent airflow under the floor rather than pushing it outward along the sides—further reducing overall aerodynamic efficiency. Although teams will inevitably try to circumvent the rules, early estimates suggest an initial downforce reduction of roughly 30%. Overall grip should still remain very high, though not at full ground-effect levels, likely around CL ~3.5–4.0 early in the cycle, while drag coefficient should fall well below Cd = 1.0 even with closed wings—and potentially around 0.6 with wings open.

One surprising but logical consequence: braking distances may increase significantly (quoted at 15–20%), because both downforce and drag decrease, reducing normal and longitudinal force on the tyres during braking. That should be a further step towards more overtaking. Last year at the end of Monza’s main straight, the late brakers hit the pedal around 110–115 metres from ~345 km/h. This year, that may move closer to ~140 metres to make Turn 1. That’s assuming similar top speeds—but in 2026 many cars will arrive at the end of long straights at lower speeds due to energy saving, so the real-world increase may often be closer to 5–10%.

The Internal Combustion Engine: Less Fuel, New Constraints

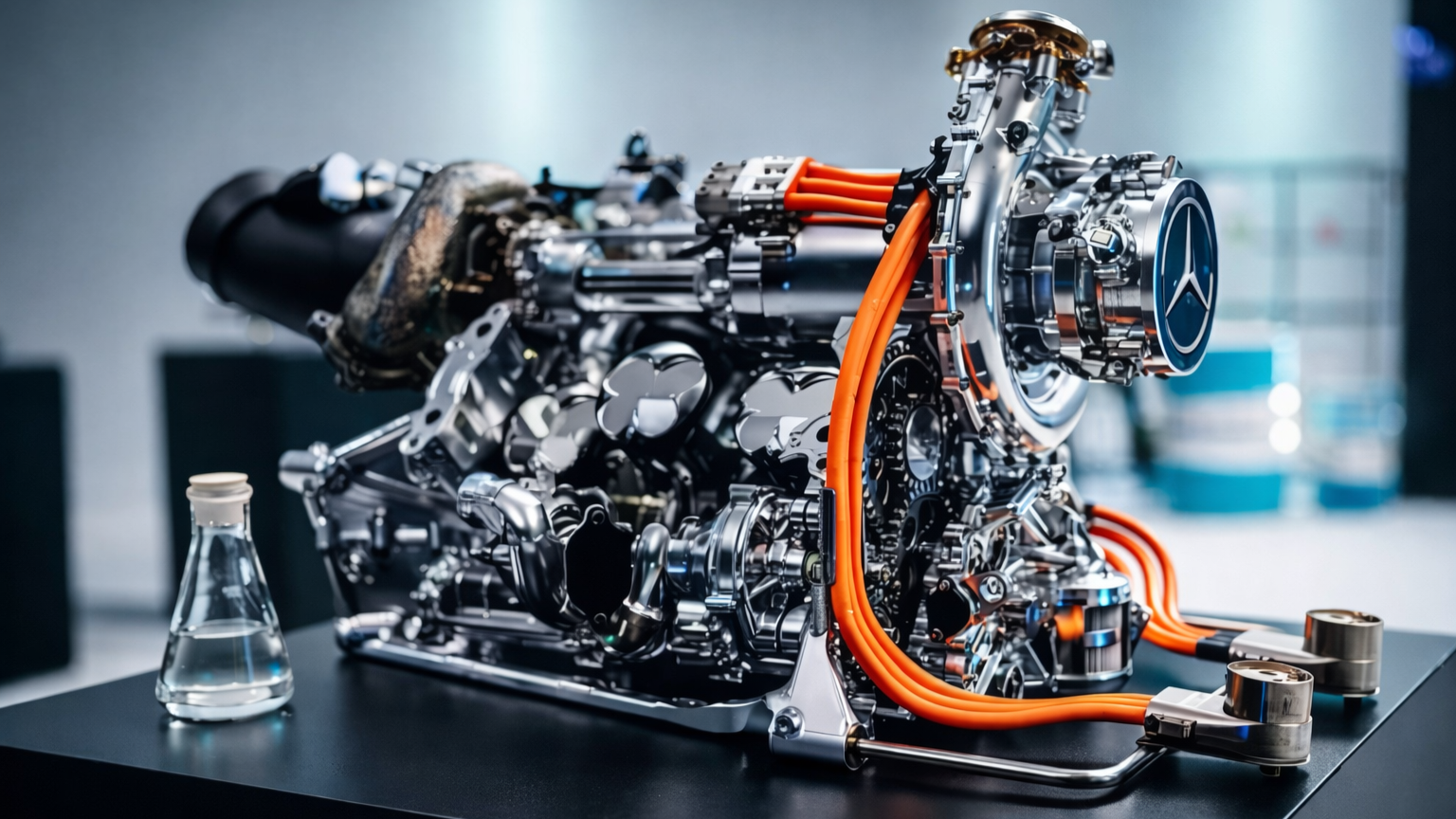

On the power-unit side, one of the biggest changes is the disappearance of the MGU-H. With it gone, the classic turbo-lag problem re-emerges. Throttle response and drivability must be recovered by other means—and although engine rules are strict, a softer form of anti-lag style calibration is likely to return: valve overlap, minimal injection and ignition, and that distinctive “machine-gun” crackle last heard prominently in the blown-diffuser era at corner entries. The goal this time is simply to keep turbo speed alive—though not with the same effectiveness as an MGU-H spinning the turbo to maximum RPM. Because extra heat energy is no longer recovered from braking the turbo-shaft, the turbo itself can shrink, meanwhile boost pressure is capped (4.8 barA). The ban on variable intake systems will also worsen the torque characteristics compared to last season.

Total power-unit minimum mass rises from 151 kg to 185 kg. Within that, the V6 must be at least 130 kg, the battery 35 kg, and the MGU-K at least 20 kg. Steel-alloy pistons become mandatory (≥350 g), and compression ratio is reduced to 16:1 (more on that below). The old 100 kg/h fuel flow limit is replaced by an energy limit of 3000 MJ per hour. In practice, that means roughly 30% less fuel energy is available, and that is the main reason V6 power drops—from the previous ~580–600 kW range to roughly ~400 kW. There is no absolute mandatory 400 kW cap; it’s a simplifying headline number. Actual output will depend on each manufacturer’s solutions.

That reduced ICE output is complemented by a much stronger energy-recovery system: 350 kW (476 hp) of MGU-K power, with up to 500 Nm of torque support, enabling peak combined outputs comfortably above 1000 hp when fully deployed. As a result, acceleration will be spectacular—especially in the 160–320 km/h range where traction is no longer the limit but the FIA’s ERS power ramp-down hasn’t yet become dominant. In the first half of many straights, the cars will look like rockets.

The 3000 MJ/h limit also pushes manufacturers to chase even higher ICE efficiency. Today’s V6s already operate around ~50% thermal efficiency, and maintaining—or improving—that figure with new fuels and lower compression is a major challenge. At 50% efficiency, the rules translate to roughly 416 kW from the ICE; each additional percentage point is worth about 8.3 kW. That’s why the rumoured “compression trick” drew so much attention—solutions that effectively reduce combustion chamber volume under load (while avoiding knock) could unlock meaningful efficiency gains.

But compression is not the only headache. Injection pressure drops from 500 bar to 350 bar, and pre-chamber ignition—so effective with lean combustion—gets harder. Instead of up to five sparks per cycle, the mixture may now be ignited only once, and ignition energy is capped at 120 millijoules. You can no longer “machine-gun” micro-sequence sparks to light extremely lean mixtures and shoot flame like a jet torch into the main chamber. This doesn’t kill pre-chamber ignition, but it could reshape it and reduce its effectiveness. Either way, this area will be a key battleground for improving V6 efficiency, which is why the concept of a deliberately extending/elongating connecting rod to enable higher compression was one of the main topics of the off-season.

If a solution matches official measurements, it is legal: thermal expansion has always been part of engine reality, as components inevitably stretch and deform under hundreds of degrees and massive pressures. Ferrari may have explored a different approach by increasing steel usage, since a cylinder head that stretches less under 250 bar+ peak pressures and tolerates higher chamber temperatures could be beneficial—if the performance gain outweighs the penalties of extra mass and a higher centre of gravity.

A practical change for race preparation: the old 110 kg race fuel limit is gone. It no longer makes sense—carrying more fuel doesn’t allow extracting more than 3000 MJ/h anyway, so the only “benefit” would be self-inflicted weight. Teams were already underfueling their cars for optimal race weight in previous years, yet they still had some flexibility.

A key early-era balancing mechanism is also introduced: a two-stage catch-up system called ADUO (Additional Development and Upgrade Opportunity). Every six races, the FIA will assess power-unit performance metrics over that period. If a manufacturer is 2–4% behind, it receives one extra homologation opportunity in that year and the next; if it is more than 4% behind, it gets two extra opportunities in each of those years. The aim is to avoid a repeat of the early hybrid era, when Mercedes dominance persisted for years.

Customer teams can still lease hybrid power units at a fixed FIA price—€20,750,000 per year, including engineering support—and can still purchase the associated fuels and lubricants, which will be especially crucial in the synthetic-fuel era. In year one, teams may use 4 engines, 4 turbos and exhaust sets, and 3 batteries, MGU-Ks and control electronics; from year two, each allowance drops by one.

Energy Recovery: More Powerful, More Demanding, More Strategic

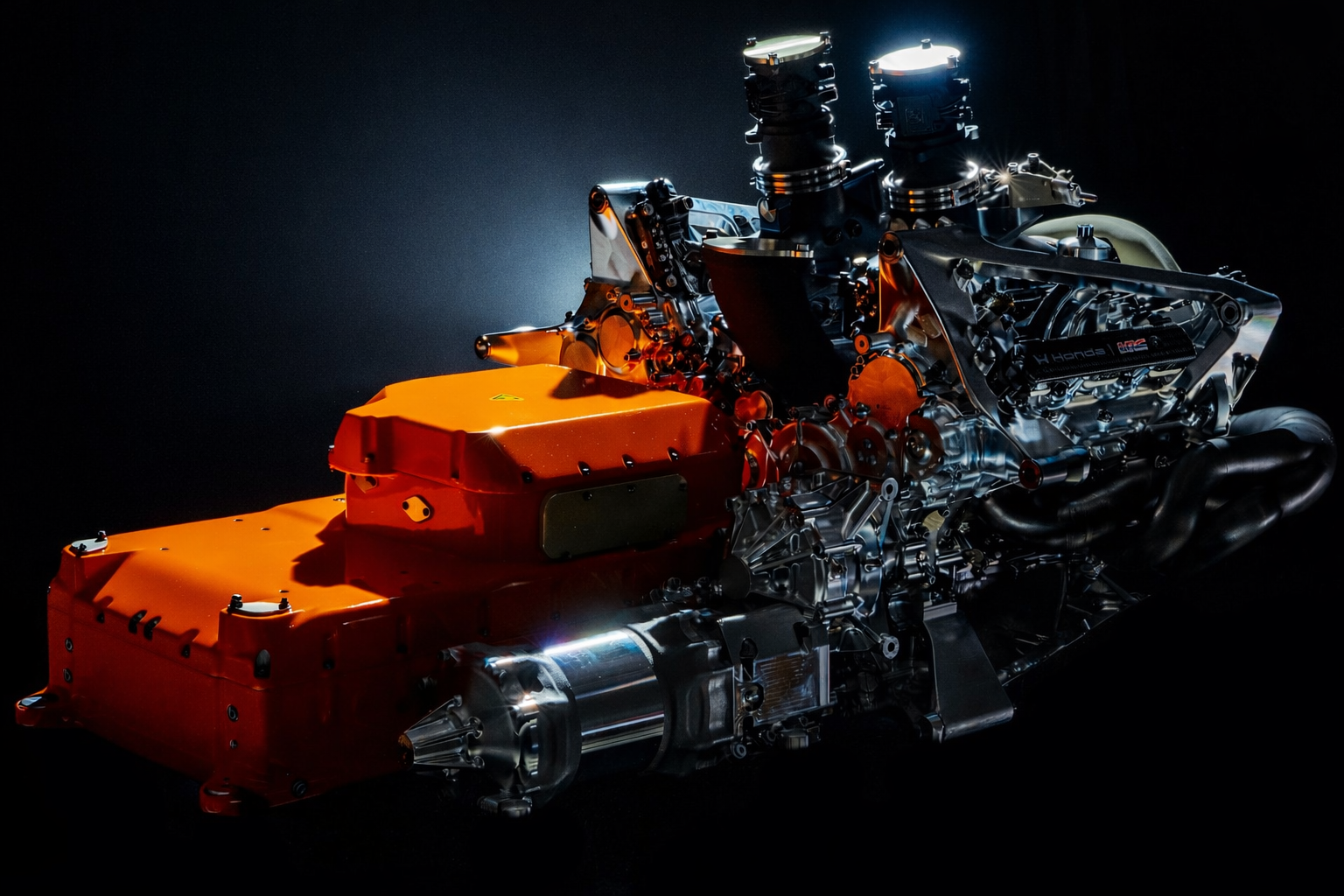

In raw energy contribution, the split will often be around 55–45 in favour of the V6, and this is even more true when considering the average available power. The ICE could and will be a big performance differentiator in 2026, yet the overall system will feel more ERS-dominated than before driven by the threefold increase in electrical power versus the previous era—despite losing the MGU-H, which used to be the hybrid system’s ultimate wild card.

In the previous 120 kW era, the turbo-shaft energy unit could effectively do whatever the system needed: e-boosting the turbo on exits, sustaining turbo speed on overrun and recovering energy, charging the battery even at full throttle, or smoothing virtually any hybrid programming problem. In the early hybrid years, exploiting this potential was often the difference between winning and losing. But it was complex and had limited road-car relevance, so removing MGU-H became the major “sacrifice” to attract new manufacturers—especially with Audi joining.

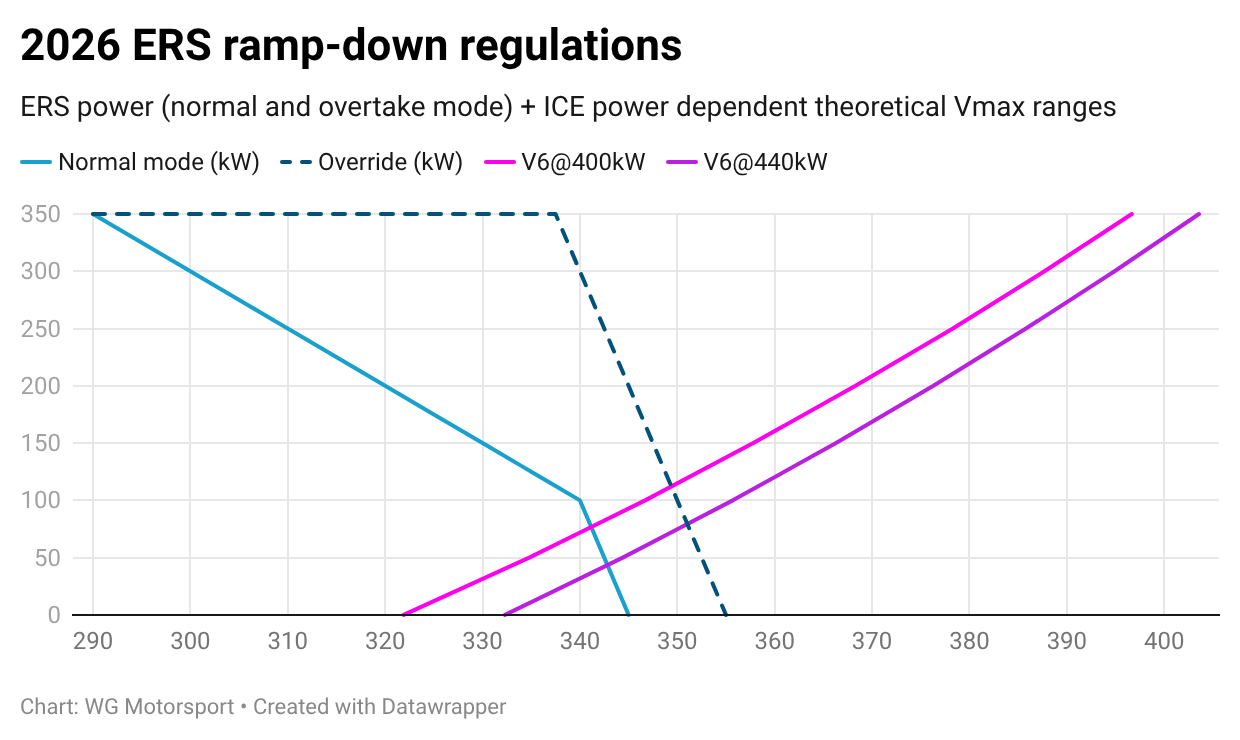

In exchange, the kinetic system is nearly tripled: 350 kW (476 hp) can be deployed for propulsion. Per lap, teams may normally use 8.5 MJ, plus an extra 0.5 MJ in overtaking mode—available when a car is within one second of the one ahead. This replaces DRS as the main overtaking weapon: speed differences are created by power deployment, not a rear wing flap, on designated sections above 290 km/h.

Here’s the twist: the battery state-of-charge swing remains capped at 4 MJ. That forces teams into continuous “charge ↔ deploy” cycling within the lap. You cannot simply accumulate 8.5 MJ and fire it all at once—neither in qualifying nor in the race. At maximum 350 kW, a 4 MJ swing corresponds to about 11.42 seconds of full deployment—then you must recharge, or you break the rules. Of course, nothing forces teams to run maximum ERS power constantly, so there is massive strategic freedom—more on that later.

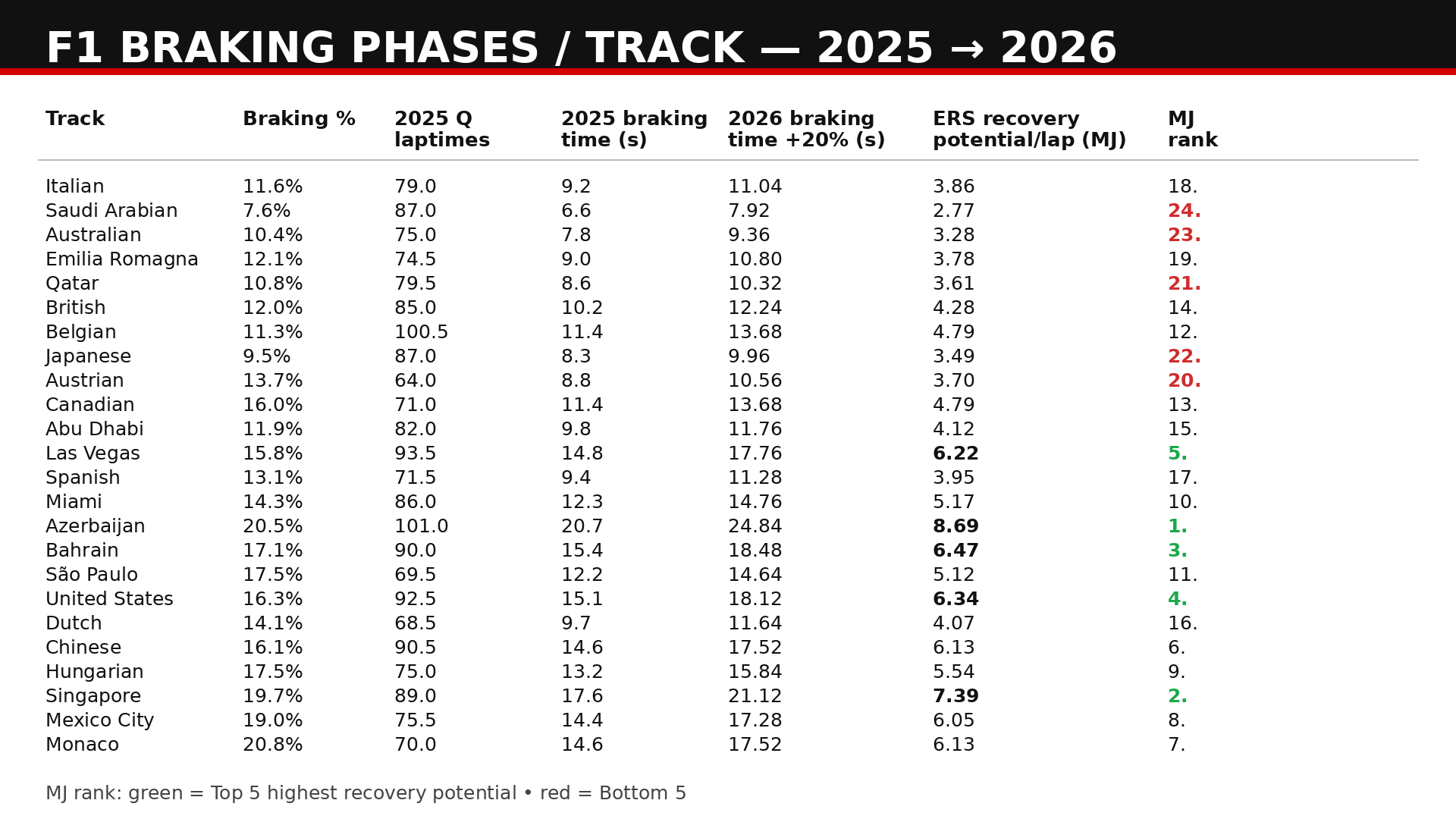

Energy needs and recovery potential vary by circuit, driven mainly by how many heavy braking zones exist and how intense they are. That’s why the FIA can adjust the 8.5 MJ baseline per track. On energy-hungry circuits like Jeddah or Monza, qualifying may allow 5 MJ, while races may allow 8 MJ. On tight street tracks, ERS may be run below 350 kW to avoid unrealistic speeds between the walls. Circuits may also be categorised by power demand depending on whether full-throttle sections are longer or shorter than 3500 metres. Fun fact: without FIA restrictions on ERS usage, a full-power lap would require around 13–15 MJ of energy from the hybrid system.

The three-times-stronger system also transforms battery design. With only a 4 MJ usable range, the system must cycle aggressively; a “barely 4 MJ” battery delivering 350 kW would face extreme current draw and thermal stress. In practice, teams will favour power-dense cells, heavy cooling, and often a higher nominal capacity so the 4 MJ swing happens in a gentler SoC window. From a heat/resistance/longevity standpoint, an optimal solution is likely a 4–6 kWh high-power battery, rather than an ultra energy-dense one. This contributes heavily to the overall power-unit mass increase: MGU-K mass rises to at least 20 kg, and the battery to at least 35 kg—targets that may not be trivial to reach in the first year.

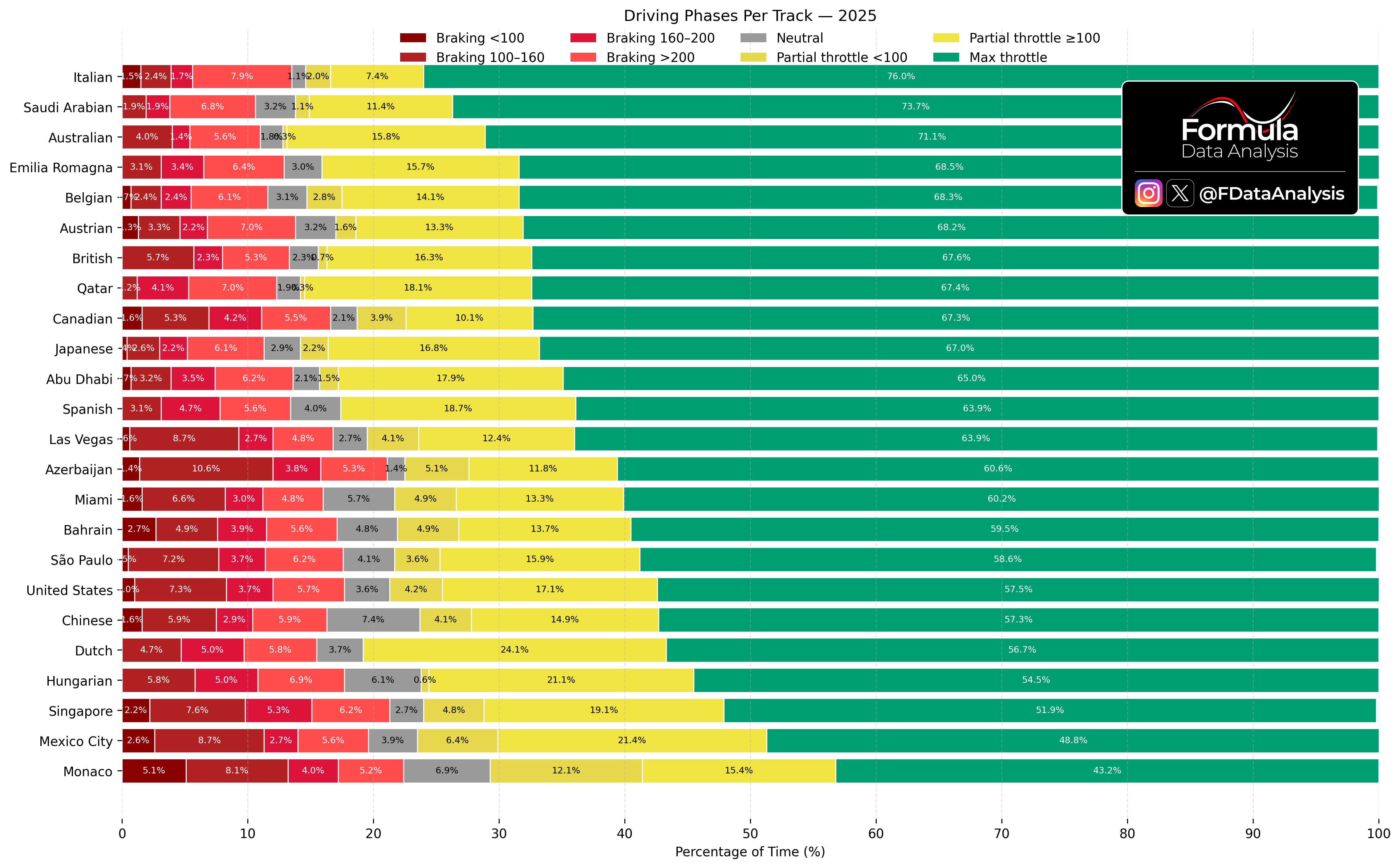

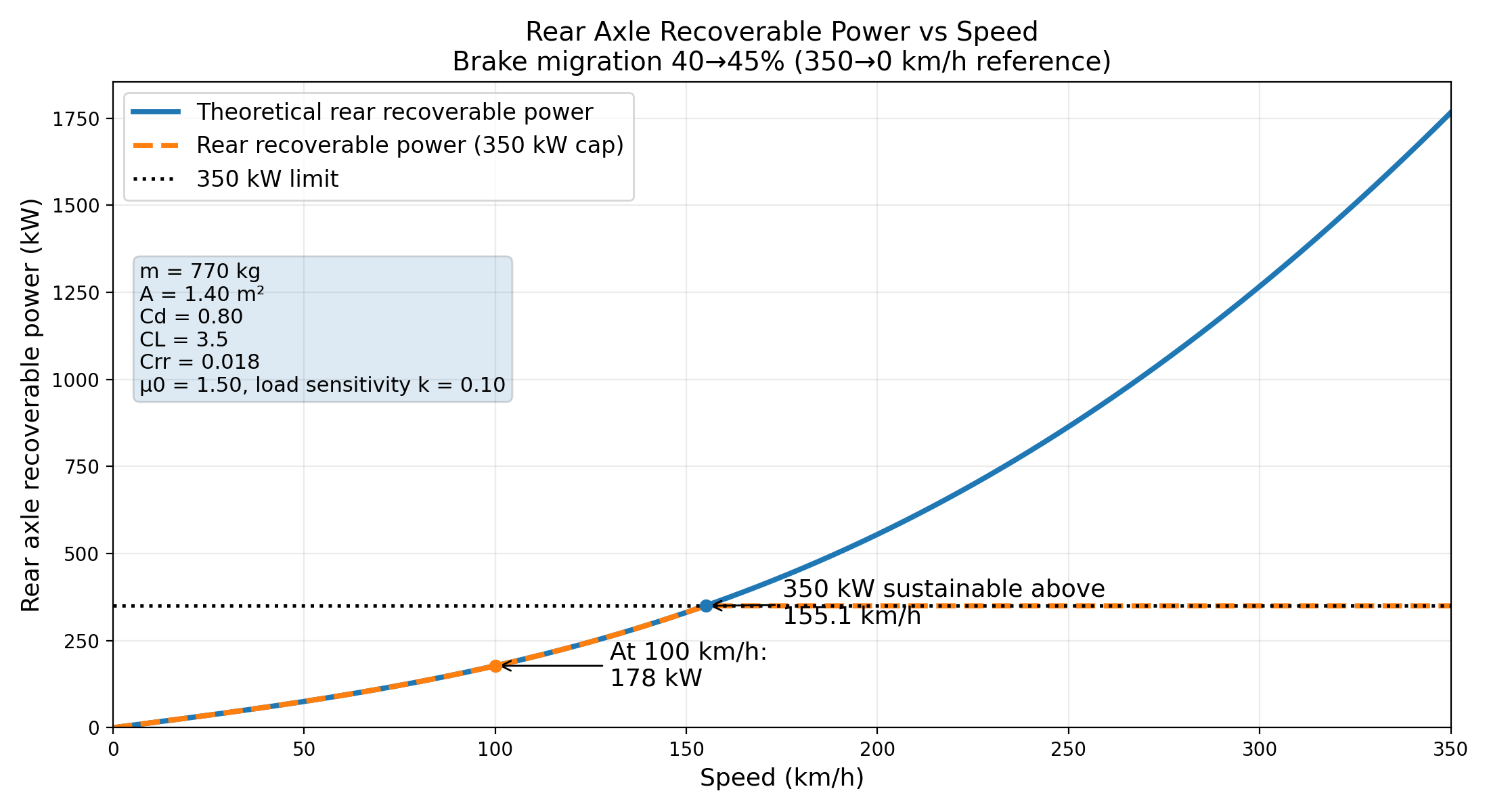

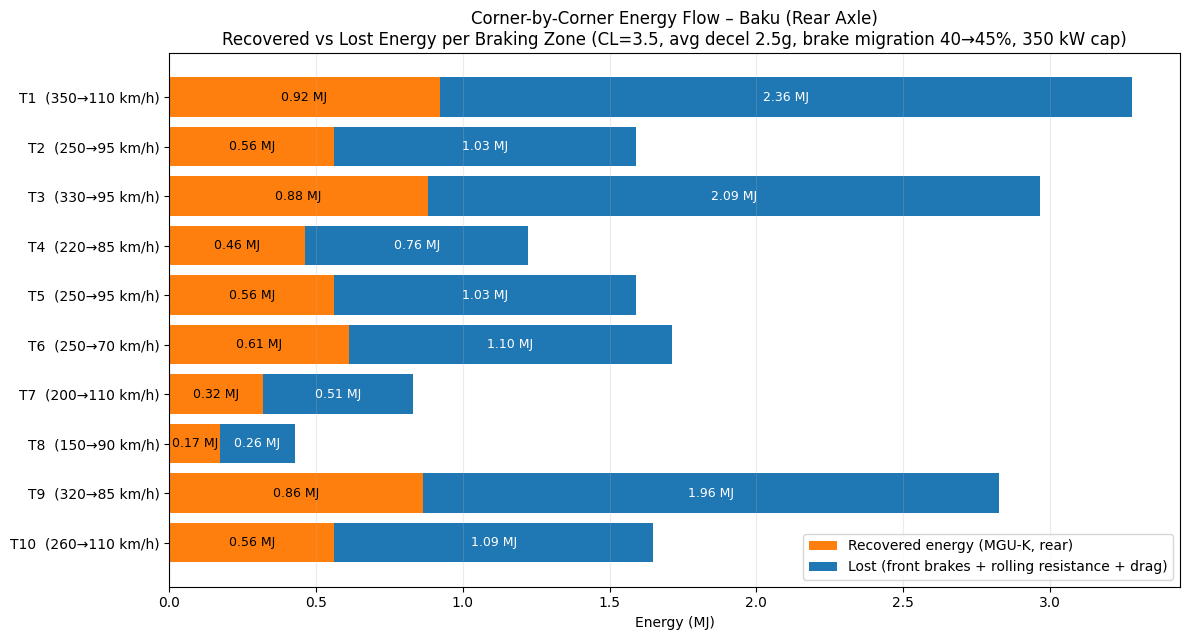

From an energy-recovery perspective, 2026 may become a fight against near-constant energy deficit, because recovery comes only from braking the rear wheels—more precisely, the crankshaft via the driveline. The limiting factor is the 350 kW cap: it is triple the previous rear-axle generator braking, yet still insufficient to harvest the full potential of heavy braking zones. Even at maximum braking intensity, only 0,35 MJ per second can be stored. As downforce falls during braking and the rear axle unloads, around 160 km/h the recoverable kinetic energy may drop below the ideal for sustaining maximum recovery. That will create huge differences between circuits—something that existed before, but the MGU-H could fill many gaps. Now teams must generate at least 8.5 MJ per lap from deceleration alone.

Looking at the table, it becomes clear that in theory only Baku could recover the regulation-allowed 8.5 MJ per lap purely from braking, if every braking event were carried out at maximum recovery! This is further helped by the fact that braking zones are expected to become longer this year, allowing energy harvesting to be sustained for longer periods. In the largest deceleration zones, around 0.75–0.9 MJ can be transferred into the battery, while on most circuits a lap-total recovery in the 4–6 MJ range appears realistic. The overall average stands at 5.18 MJ per lap, with a median of 4.97 MJ.

By contrast, circuits characterised by fast corners and long full-throttle sections (Jeddah, Melbourne and Qatar) will pose a serious challenge, with charging potential typically limited to around 3–4 MJ per lap.It is also important to stress that these figures represent net theoretical values and do not include conversion losses, which must inevitably be accounted for in real-world operation during energy transfer into and out of the battery.(Special thanks to Mirco, the founder of Formula Data Analysis, for collecting last year’s baseline data for the table.)

That’s why engineers will try to create recovery opportunities elsewhere, within tight regulatory limits. One method is partial-throttle harvesting: when the driver goes back to throttle in a corner but is still far from demanding full power, the V6 isn’t at 100% either. If the MGU-K harvests only the excess crankshaft power above the driver’s requested wheel torque—without reducing what the driver asked for—then it can be legal. In practice this is micro-harvesting at the start of exits, typically only 40–80 kJ depending on corner type and grip, because once you need ERS propulsion, the MGU-K can no longer operate as a generator. The upper limit for partial-throttle harvesting will be around 100–120 km/h, so not all corners are suitable for it.

Then there’s the classic lift-and-coast: lifting early before the braking zone, with no brake pedal yet. Above 300 km/h, the MGU-K can begin rear-axle generator braking while the driver is still coasting. The key is keeping active aero working so drag doesn’t do all the deceleration; you want as much as possible to be generator braking. With good timing and limited lap-time loss, another 150–200 kJ can be recovered before braking even begins.

What you will not see is engines “screaming” at corner entry to harvest energy. The system cannot disengage the clutch, and even if someone tried to recover in that way, the V6 would not roar—because you would need to brake it, not free-rev it. Fuel-energy rules also prevent it: in engine-braking operation (from −50 kW), only one-eighth of the normal fuel energy is permitted. Likewise, “braking against full throttle on the straight” is not allowed: with positive throttle demand, generator mode cannot be used to brake the ICE. That is only permitted when the driver is no longer requesting propulsion (throttle lift). Otherwise, braking the rear axle against full throttle would conflict with the ban on traction-control-like behaviour.

More than ever one of the key tasks for hybrid-system engineers remains to be to find the optimal energy deployment map for each circuit – in other words, the software strategy that delivers the fastest possible lap time. This, however, applies mainly to the ideal case, most notably in qualifying. For the race, a wide range of alternative maps will be required, depending on tyre compound and condition, whether the driver is running in traffic or in clean air, and whether they are defending or attacking. And when the driver steps in, the system has to react in an instant and rewrite the plan on the fly for the remainder of the lap.

Depending on design philosophy and harvesting strategy, rear brake sizing could diverge significantly—as Brembo has already hinted—because nobody yet knows the true optimal mix for rear-axle energy recovery. Haas team principal Ayao Komatsu even noted that in Barcelona testing everyone will be focused on optimising energy usage, and teams will need quick answers to open questions.

Fuel Revolution: Sustainable, Synthetic, and Strategically Different

From this year, Formula 1 switches fully to 100% sustainable fuels, largely synthetic. Fuel development is a cornerstone of the new era, aiming to prove sustainable operation for internal combustion engines. Each manufacturer works with its own fuel partner after years of lab development, often taking very different approaches to the chemistry puzzle. Aramco, BP-Castrol, ExxonMobil, Petronas and Shell may play a decisive role in refining combustion and extracting extra performance from engines tuned to the absolute edge of efficiency.

These fuels—up to 102 octane, using advanced bio components or fully synthetic “e-gasoline”—will have very different molecular make-up compared to traditional hydrocarbon blends. Feedstocks may include non-food plants, organic waste, sewage sludge, biomass, micro- and macro-algae, engineered bacteria, and even processes based on water and air. The goal is always the same: end up with hydrocarbons after an energy-intensive chain. Ethanol from algae photosynthesis sounds like science fiction; so does fuel made by capturing carbon from air and combining it with hydrogen from water splitting—yet these are no longer purely imaginary, even if they are not everyday pump products (yet).

The key engineering challenge is calibration from scratch: achieving maximum efficiency with unfamiliar components, tailored to each manufacturer’s engine concept and development targets—while dealing with a fuel that may be more aggressive toward materials, especially seals. And fuel impacts development beyond chemistry: different atomisation and burn behaviour may force changes to ignition and injection components and strategies.

Beside the 3000 MJ/h limit, the rules also constrain fuel energy density (lower heating value) to 38–41 MJ/kg. Converted into mass flow, that’s 73.17–78.94 kg per hour, or 20.3–21.9 g per second at maximum power. A lower-energy fuel allows higher mass flow, but it also means teams must start heavier. In the worst case, that could mean 8–9 kg extra at the start of a 90-minute race—potentially 7–8 seconds of total race-time loss.

But energy density is not the only lever. Combustion efficiency and knock resistance become central, so the “best” fuel may not simply be the one pushed to 41 MJ/kg. With V6 efficiency becoming the main determinant of ICE performance, properties like spray pattern, knock tolerance, burn speed, and combustion stability become crucial—and there is no magic blend that maximises everything. What helps heating value may hurt burn speed; what increases density may worsen atomisation. Success will come from balancing trade-offs tailored to each engine.

Key challenges in developing sustainable F1 fuels

-

• Increasing burn speed

-

• Optimising laminar and turbulent combustion behaviour

-

• Improving knock resistance under a 102-octane cap

-

• Optimising latent heat of vaporisation and charge cooling

-

• Matching spray pattern and mass flow to direct injection + pre-chamber systems

-

• Optimising heating value for mass reduction → fast burn vs. high LHV

-

• Optimising density for volume reduction → dense fuel vs. better atomisation

Once a strong base fuel exists, it can be further fine-tuned by circuit conditions. Hot, high-load tracks may prioritise charge cooling; cooler venues may favour higher energy density; high-altitude races increase the value of perfect mixture formation and ignition stability.

In short: the 2026 rules reward efficient combustion, not simply “energy-rich” fuel. The ideal sustainable F1 fuel burns fast, resists knock, atomises cleanly, and provides strong charge cooling. The winning formula in coming years likely won’t be the “most powerful” fuel on paper—but the one that burns most efficiently in a given engine.

Racing Impact: More Active Driving, More Strategy, More “ERS Chess”

Shorter, lighter cars with less overall downforce will be more agile and responsive—but also less “on rails.” They’ll likely demand more subtle, continuous driver input. At the same time, they should become easier to manage right on the edge of grip: higher ride height, softer springs and longer suspension travel all make that knife-edge dance more controllable. On corner exits, drivers will have to keep working the throttle, because with the new torque characteristics and less donwforce the driven wheels can still brake traction even above 150 km/h—and the same applies in reverse under braking, as significantly longer braking zones change how the car needs to be slowed and stabilised.

In slow, tight corners and chicanes, the reduced mass and shorter wheelbase should bring a clear improvement, with sharper direction changes and less understeer. As speeds increase, however, the cars are likely to become more nervous, and sections that could be taken flat in the ground-effect era will once again turn into real corners. Copse, Abbey, Pouhon, Dunlop or Barcelona’s Turn 9 are expected to require a lift again this season – and not only because of the drop in downforce.

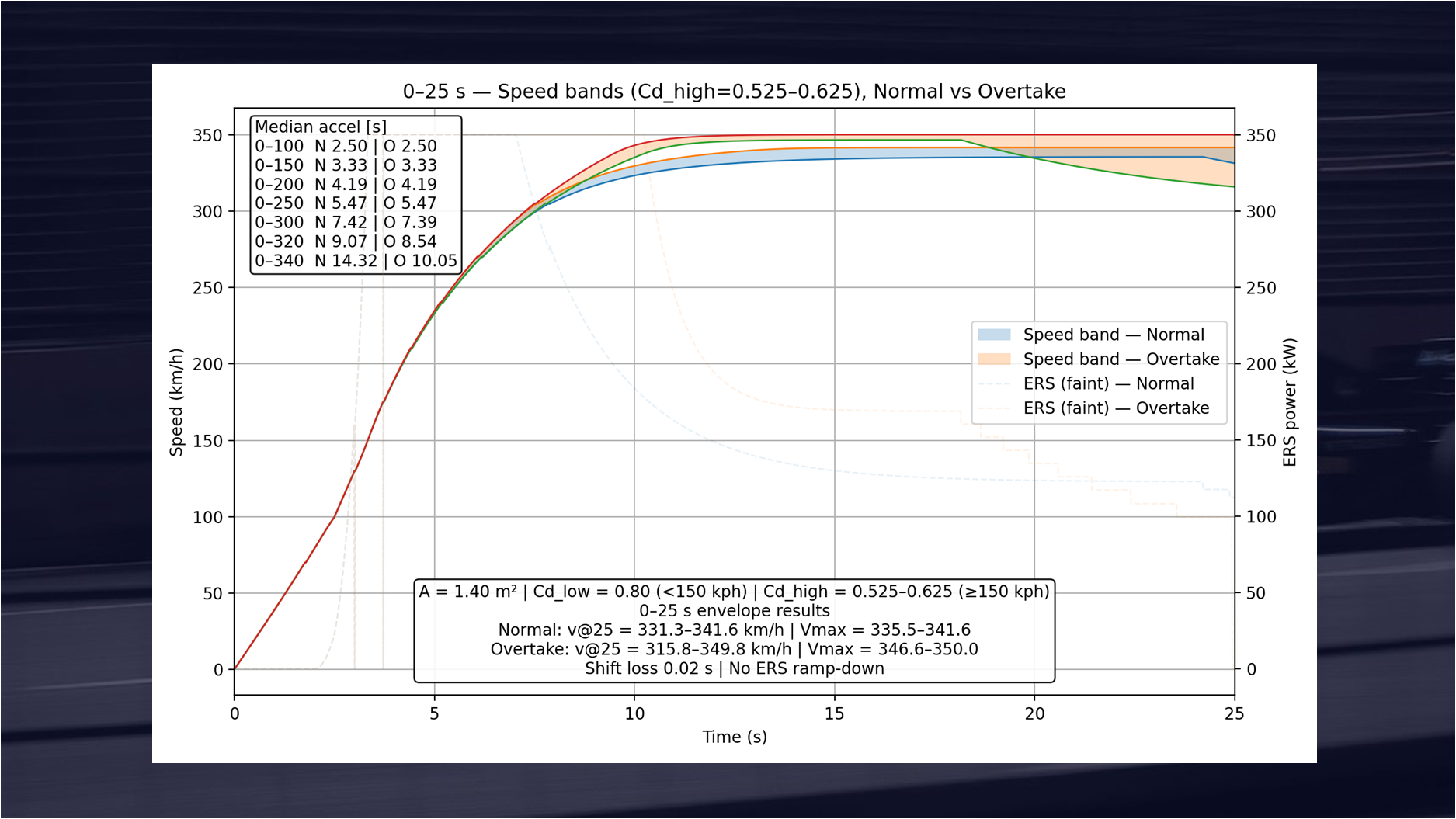

This year’s cars will also feature extreme acceleration performance in the 160–320 km/h range, operating in an almost different dimension compared to the ground-effect generation. Thanks to active aerodynamics and extra horsepower, they will arrive at many corners at speeds we simply haven’t seen before – something that will be especially striking in qualifying. While acceleration from 0–160 km/h will be broadly similar, above that threshold the new cars will leave the 2025 machines behind: reaching 300 km/h roughly four seconds earlier (around 8.0s), and 320 km/h 8–9 seconds sooner (around 10.0s) than their predecessors.

Contrary to the earlier rumours spread by Toto Wolff the cars will not be running at 400 km/h. That speed would only be theoretically possible if there were no per-lap energy limits and no ramp-down reduction of ERS power above 290 km/h. In reality, on most circuits the top speed will be in the 340–360 km/h range, depending on the track and engine mode. However, this peak speed will not be reached at the very end of the straights, but rather around the middle of them. From that point onward, the speed will decrease slightly towards the braking zone, depending on V6 engine power, aerodynamic drag, and the chosen ERS recovery strategy.

Cars will also be considerably lighter at the start of races—not only because of the roughly 30 kg minimum-mass reduction, but also because the new rules mean carrying around 25–30 kg less fuel for the race distance. That lowers the load on the tyres in another meaningful way. The rears, however, will immediately feel the punch of the much more available torque on corner exit, so tyre management may become—more than ever—a question of keeping the rear tyres under control. In that sense, the best “throttle whisperers” may be rewarded. That fine throttle work won’t be made any easier by a rougher, less refined engine response, with turbo lag more or less returning as the MGU-H disappears.

Even though the cars shrink, losing 30 kg will not be straightforward. A much more powerful ERS system, a new dual-crash-structure nose and a host of smaller regulatory changes all add pressure to the weight target. As a result, cars that start the season overweight could find immediate lap time through a successful “diet” in the development race—while the teams that hit the minimum weight from day one will enjoy that advantage immediately, measured in tenths.

A question many people are asking is how much lap times will increase compared to today, and there is no exact answer to that. As an order-of-magnitude estimate, something in the region of 2–3 seconds per lap seems plausible, but this will strongly depend on each circuit’s energy recovery potential and layout characteristics. On tracks where energy recovery is difficult, full-throttle percentage is high and cornering speeds are also high, the lap time loss is likely to be greater, e.g. in the extreme cases of Monza or Jeddah possibly more than 4 seconds slower. Conversely, on stop-and-go circuits, especially street tracks with relatively short straights and few high-speed corners, lap times similar to earlier could still be achievable — provided the FIA does not significantly restrict ERS power at those venues on safety grounds.

Driver workload will increase too. It won’t just be about opening the active aero at the start of every straight: drivers will be managing ERS continuously, and overtaking will involve a dedicated deployment request when they are within one second of the car ahead. The speed advantage is only realised above 290 km/h, where the attacking car’s control strategy can allow maximum power up to roughly 337.5 km/h, while the car ahead receives progressively reduced electrical assistance. That extra pace comes at a price: it consumes energy fast— 0.35 MJ per second—so the “overtake” button can’t be used blindly.

In a way, 2026 introduces the era of “ERS chess.” With smart harvesting and timing, you won’t only be able to “checkmate” an opponent with a classic out-braking move—you can set up the pass earlier with energy strategy. Early on, teams and drivers will test many approaches before the practical optimum emerges, but the game will remain dynamic throughout the season. And it won’t be decided only by software: the driver’s situational awareness will matter just as much as the hybrid control electronics.

One principle will be self-evident: to produce the best lap time, stored electrical energy should be deployed at the very start of acceleration zones to build speed early, then “ride” that speed deep into the straight. In the final quarter of the straight, before the braking zone, drivers can begin to lift and coast—using engine braking to drip energy back into the battery—before the main harvest begins under heavy braking.

Attack and defence will also evolve in unexpected places. Shorter straights may create opportunities that force different racing line choices from the car ahead. In those situations, a form of pre-emptive defence may be to move to the inside from mid-straight, so a sudden power burst from the car behind can’t claim the inside position before the braking zone. The same logic applies to reading an opponent’s energy state: because continuous harvesting becomes necessary, it matters where and for how long each driver charges the battery. The ERS control will try to optimise this automatically, but only the driver truly sees the race situation in real time—and can adjust it with “boost” or “overtake” deployment.

In traffic, cars will inevitably try to gain advantage by saving energy, effectively fighting kilojoule by kilojoule, so that when the moment comes they can strike with momentum against the cars ahead. For the same reason, defending won’t always be the best option: if letting the other car through makes more strategic sense from an energy perspective, you might allow it—then counter-attack later when the energy picture flips. On some tracks, this could even produce situations reminiscent of classic oval-racing slipstream battles, where you want to exit the final corner in second place because the leader “punches the air” all the way to the line—and you pass with the run. Of course, that only holds when ERS efficiency and overall power-unit performance are broadly comparable.

2026 will therefore bring truly far-reaching changes for teams, designers, and drivers alike, and these challenges are so complex and wide-ranging that it is almost impossible for anyone to get everything right on the first attempt. The first test week will essentially be spent on continuous system checks for everyone, focusing on understanding the new engines, fuels, and this year’s hybrid systems. The goal is to ensure that by the time the field relocates to Bahrain, meaningful development work can already begin.

Meanwhile, the clock is ticking fast: in just over a month, the race-ready cars will already need to be shipped to Melbourne.

Disclaimer: 2026 data was generated with the following estimated values - A=1.4, CL=3.2-3.8, Cd=0.8/0.6, Crr=0.018, η_dt=0.93, m=770 kg, P=750 kW (400+350)

Photos: Formula 1, Honda Racing Corporation, Mercedes F1 Team, Scuderia Ferrari, xpbimages.com, @jancikapral

Graphs: Formula Data Analysis, WG Motorsport